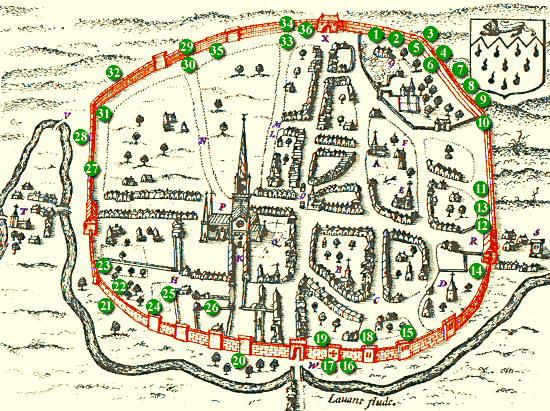

Image courtesy of Chichester Web. This article forms part of a series on the archaeology of Westgate and is adapted with their permission from an archaeological desk-based assessment prepared by SLR Consulting Ltd on behalf of Chichester College in 2013. The numbers on the map refer to objects mentioned in the text below that have been found and registered in the Historic Environment Record (HER) for Chichester District.

Early Medieval (5th – 11th centuries AD)

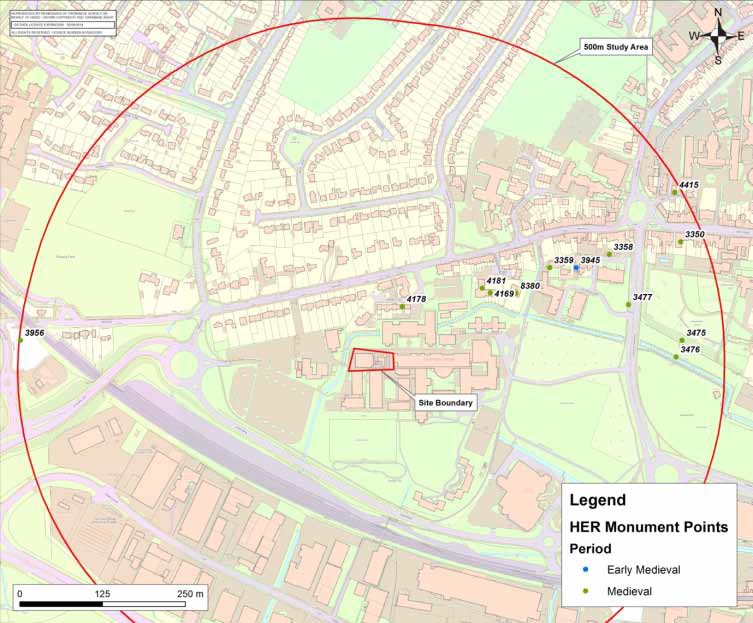

The archaeological record for Chichester in the early medieval period is limited. Within 500m of Westgate there is a single recorded asset; a ‘silver coin of Alfred’, discovered in 1871, around 125m to the northeast of the college near to the Theological College (HER 3945).

This single find perhaps does not reflect the importance of the burh during this period, though it is likely that most activity took place within the defended core of the town; this archaelogocial study area falls outside that area into Westgate Fields, and as the name suggests most likely fields or pasture at that time. The earliest written reference to our area appears in an undated charter in which South Saxon King Ethelbert gave “a certain parcel of land … in the southern part of Chichester (Cicestriae), close to the sea with all the fields, meadows and rivers to it pertaining” to Wilfrid, Bishop of Selsey (681–707 AD).

The presence of an earlier population however is attested to by the presence of a large Saxon cemetery dated to the mid-5th to mid-6th century at Westhampnett to the east of the city. In the late 9th century the Saxon occupants of Chichester, by then an important burh, successfully defended the city against attack from the Danes. Its position on the coast left it exposed to such attacks, and so the organisation of the city for defence was paramount.

Recent archaeological work has indicated that the River Lavant was canalised around the city walls during this period. In the ‘Burghal Hidage’ produced around the start of the 10th century or possibly earlier, Chichester was assigned 1,500 hides, and by the time of the reign of Aethelstan (925-39 AD) the city had acquired a mint, hinting at the importance of the borough.

Medieval Period (11th – 16th centuries AD)

Within the study area there are 12 non-designated assets of this date recorded. The Domesday Survey of 1086 does mention Chichester, though unusually for a county town the account is brief, recording it under the land of Earl Roger de Montgomery. At the time of the Conquest in 1066 there were 97½ ‘haws’ (or building plots) and three crofts returning £2 8s. 11d. A total of 135 haws were attached to outlying manors, 37 of which were in the Rape of Chichester and three in the Rape of Arundel:

“In the City of Chichester before 1066 there were 100 sites less 2 ½ and 3 crofts. They paid 49s less 1d. This city is now in Earl Roger’s hands. In the same dwelling sites there are 60 more houses than there were before. A mill at 5s. They paid £15; £10 to the King, 100s to the Earl; value now £25; however they pay £35. Humphrey Flambard has 1 site there at 10s.” The Domesday Survey, 1066

The city was granted to Simon, Bishop-elect of Chichester, in 1204, and subsequently granted to the citizens of the city by Edward II in 1316. Between these times the boundaries of the city underwent considerable change, with a northward expansion after 1278. It is known that there was a town ditch around the northern part of the city in the vicinity of the castle, as there were continual disputes regarding its ownership and maintenance throughout the 13th century, but with the exception of the boundary formed by the River Lavant, the southern and western limits of the city were undefended.

The later medieval defences were constructed in the 14th century to include the western city limit. Excavations in 1959 at two locations demonstrated that the ditch was 15m wide and 2.4m deep, and that until later in the post-medieval period the River Lavant flowed through the ditch along the western walls (HER 3476 and 77).

The Western Suburb

The character of the western suburb of the medieval city has been demonstrated through a number of excavations which fall within the study area. Evaluation and watching brief at the site of The Tannery located two rubbish pits containing domestic refuse, and linear depressions thought to be caused by ploughing (HER 4178). A little over 100m to the east, during investigations at 6 St Bartholomew’s Close in 2003, another medieval pit was seen containing pottery of 11th – 12th century date, and a linear ditch thought to be a drainage feature (HER 4169).

The following year a limited excavation demonstrated the presence of three phases of medieval activity on the site between the 12th and 15th centuries, comprising pits and postholes some of which appeared to delineate a property or field boundary (HER 4181). Further field boundaries and pits were uncovered during excavations at the Theological College 200m to the east, also to the south of Westgate. The pottery from these features suggested that activity had occurred between the late 10th and 16th centuries (HER 3358).

An evaluation in 2010 at Mount Lane identified a single medieval pit (HER 8380). There are findspots of medieval artefacts at the south west walls (HER 3475) and Fishbone Road (HER 3956).

The focus of occupation outside the town walls was concentrated near to the West Gate, with St Bartholomew’s Church (or St Sepulchre’s Church as it was also known) at its core. The first mention of this church occurs in 1227, but the original structure was destroyed during the Civil War siege (see below; HER 3359). This event eradicated much of the western suburb of St Bartholomew.

In the medieval period the assets and activity at The Tannery would have been situated within fields to the south of the Lavant (the course of the river having been changed at a later date), adjoining those on which the college campus would later be built. There is therefore a potential for archaeological deposits to extend into the college site although any such remains are likely to be confined to agricultural features (boundary ditches, pits) and dumps of domestic refuse.