As many residents will know, Westgate, along with St Pancras, was part of the Parliamentary encampment during the brief siege of Chichester by Colonel William Waller at Christmastide in December 1642, the first year of the Civil War. Christmas 2022 will mark the 380th anniversary of this event.

A Divided City

In those revolutionary times, a clear political divide had developed between the City, the Cathedral and the local MP. Already in 1635, Nathaniel Brent, the visiting commissioner of the Archbishop of Canterbury, had been treated with disrespect. On 16 August 1642, William Cawley, the MP for Midhurst issued what is known as “The Valiant Resolution”, which declared the City’s will to support Parliament. This was unofficial however and the Mayor, Robert Exton, countered by issuing a Royal Commission of Array. This called upon all able-bodied men to take up arms for the King.

Exton then fled to the King and left it to his successor, William Bartholomew, to obtain local ordnance from Portsmouth and 200 men of the Sussex militia. The Governor of Portsmouth, Sir William Lewis, reinforced this military presence by issuing seven guns and ten barrels of powder to the Cicestrian Royalists in the November. You can still see the site of the City’s powder store today, under the East Walls at its junction with Priory Road.

Cawley and his supporters were driven for the City in mid-November by Edward Ford of Harting, who had been nominated by the king earlier that year as High Sheriff of Sussex and who now raised a small army. On the 18th, Parliament ordered him to be apprehended.

The Siege of Chichester

Waller’s forces arrived before Chichester on 21st December 1642 and spent the day constructing battering rams. Following approval from Sir Arthur Haselrig, Bt., Waller called for the Royalist garrison’s surrender through means of parley. After much debate, the garrison refused but did offer to hand over any Roman Catholics within the city walls. It is not known if this order was executed.

The Parliamentarians opened fire on 22 December and the siege lasted five days. An initial sortie through the North Gate failed, but after seven days a plan was made to attack the city from all sides, including the firing of the West Gate. The city surrendered before the assault took place, but not before the poorer suburbs of St. Bartholomew and St. Pancras had been almost completely destroyed. Ford, commanding the Royalist resistance, surrendered the City to Waller after eight days on the 29th December 1642. Despite this, Waller’s troops then proceeded to sack and desecrate Chichester Cathedral.

Using his wife’s influence with her brother General Henry Ireton to obtain his early release, Ford was knighted for his valiant efforts by Charles I at Oxford, on 4th October 1643. In our region, Waller then went on to capture Farnham, Winchester, Basing and Arundel.

The Destruction of Westgate

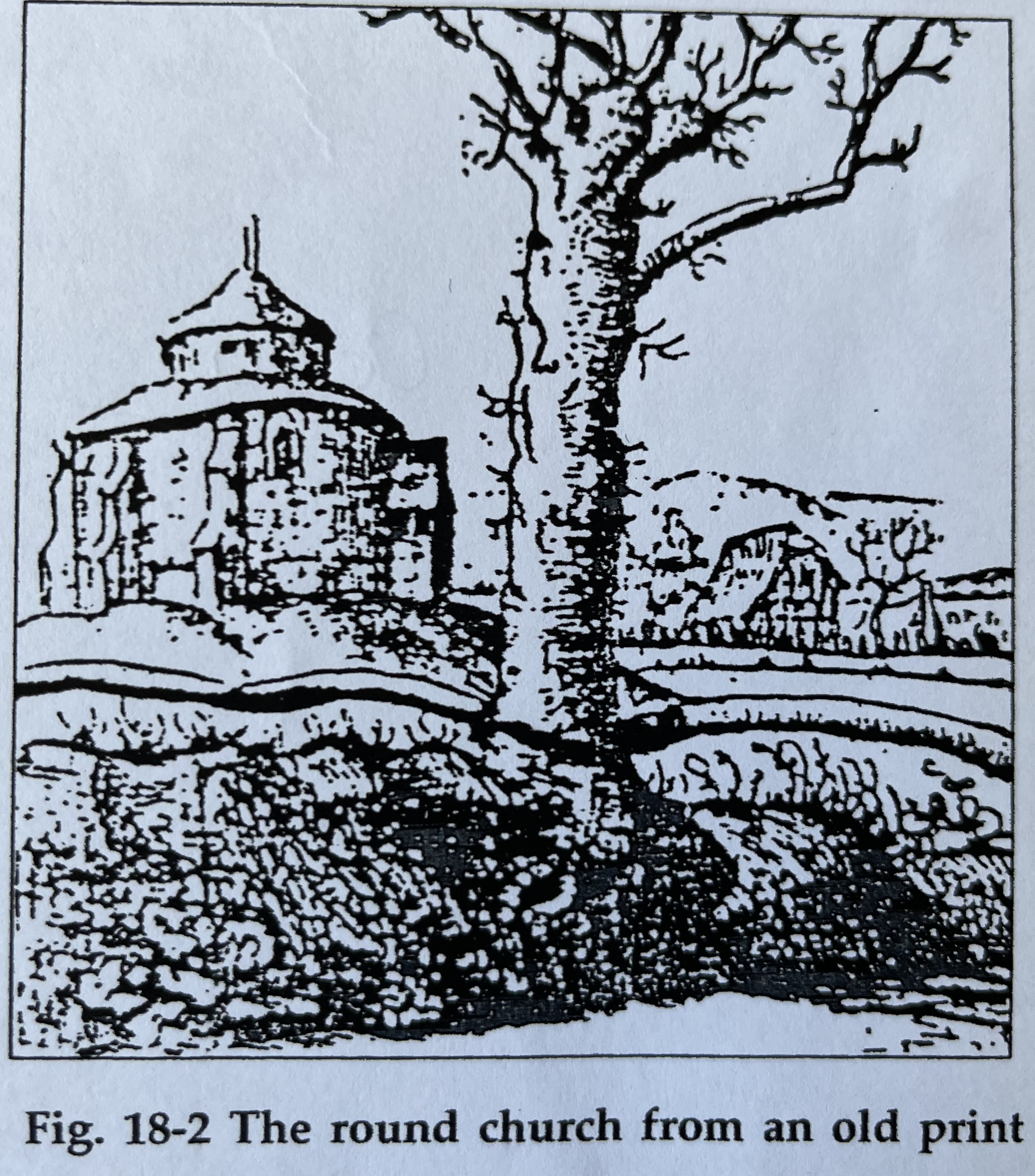

Westgate suffered terribly from this brief episode. Most buildings on the south side were demolished to give the artillery a clear line of fire over the City walls into the City. Canon were even placed on top of church towers to achieve this. St Pancras collapsed under the shock waves and The Church of St Sepulchre’s on Westgate – “The Round Church”, in what is now the churchyard of St Bartholomew’s – was demolished.

I am indebted to resident Anne Dare for drawing my attention to this rare image of St Sepulchre’s. It took 200 years for the church to be replaced

The rebuilt St Bartholomew’s Church (WSRO) complete with its tower, later removed by Max Gill during repairs in the 1920s

Parts of two domestic properties on the south side of the street did survive. These are today’s no 19, a Tudor brick and timber property which had its top storey removed to stop obstructing the line of fire. Evidence of this can be seen from the external wall visible in the gap between nos 19 and 21.

No 11 is also an ancient property, the only one surviving on Westgate with its medieval street alignment end-on to the highway and a telling lower floor level than its neighbours. This too has extant brick and timber, only visible from inside the property these days. The house may have suffered the same fate of decapitation as no 19 or could possible have survived because it was a squat farmhouse sitting on a lower street level. The earlier building sits inside a later Georgian shell extended to the rear.

Rebuilding of Westgate was slow to get organised, and it is for this reason that the streetscape on that side dates mostly from the 18th Century, whilst opposite on the north side, one can tell from the roof lines that there still remain many earlier properties whose roofs were tiled and facades refaced by opulent Georgian society during the following century. As noted elsewhere, this side of the street is an almost intact pre-Georgian row and forms a protected view within the Chichester Conservation Area.

A Relic?

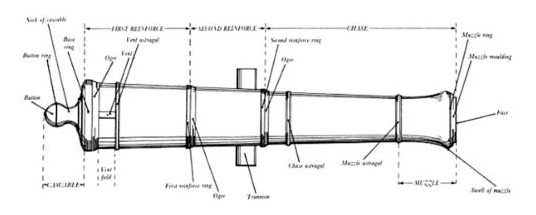

Not much remains from this period therefore, although the odd musket or cannon ball has been retrieved over time, and the beds of many of the back gardens still contain the odd shattered roof tile from the period. Few residents of, or visitors to, our street know however that urban myth has it that there does indeed remain a more important relic of this brief conflict – a cannon, pictured below.

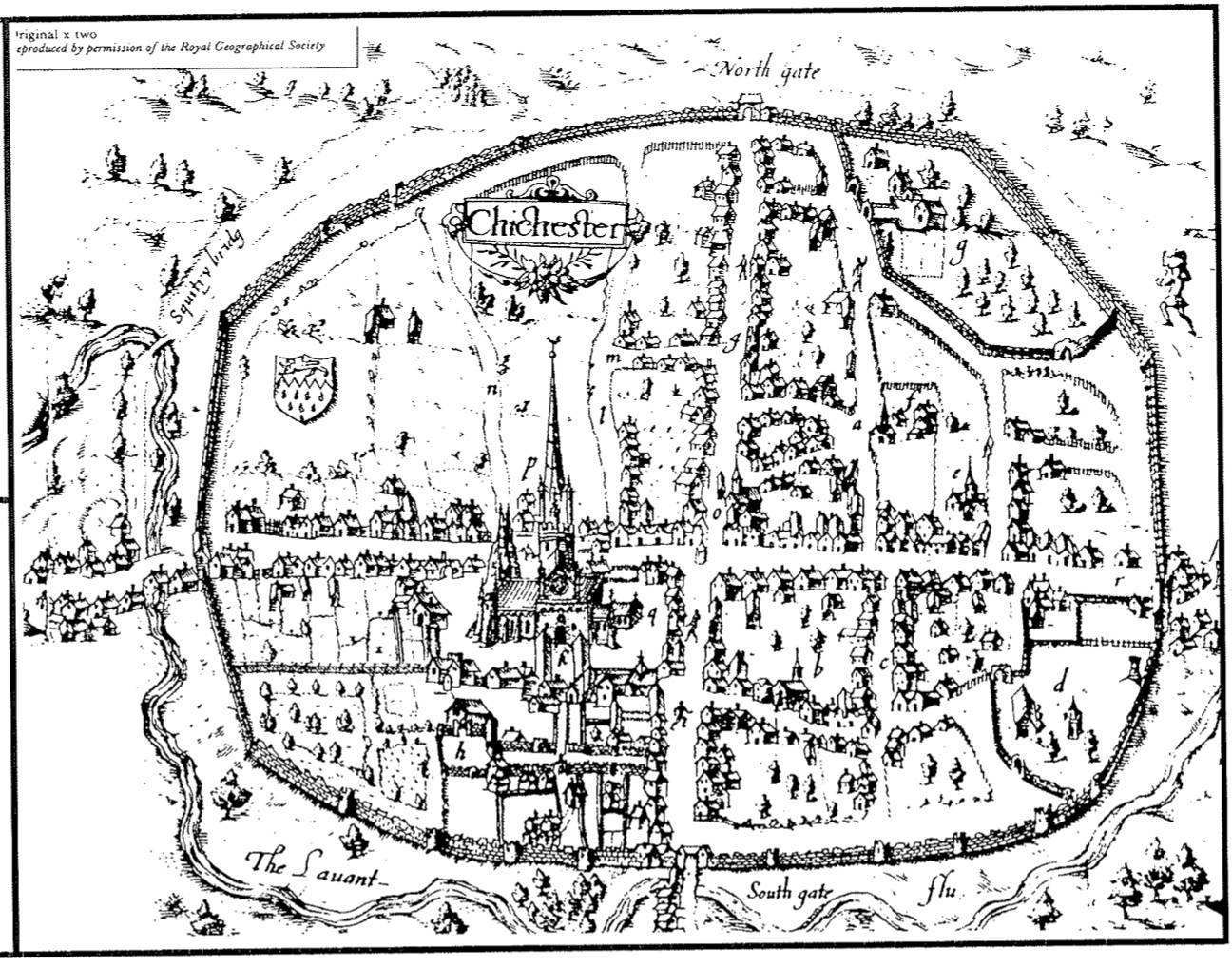

This cannon is real enough. In the late 20th Century, a large cannon thought to be from the period was discovered, mired in the mud near the Squittery Bridge. This was a crossing of the branch of the Lavant that fed the Brewery and then the Tannery, situated more or less by today’s food bank on Orchard Street. Encased these days in a culvert, the river and the bridge are clearly marked on the west side of John Norden’s map of Chichester dating from 1595.

The cannon must have fallen into the river and was much too heavy to be moved, so it lay there abandoned for 300 years. It has been installed at the entrance to Mercers’ new office block behind Westgate House for some years now, and sits buried in vegetation by their front door, safe from predatory eyes. Walk up their car park to the left of the House and see it for yourself, the genuine article and a true historic relic.

The discoverer was Allan Blamire, a popular long-standing metalwork teacher at Bishop Luffa School, who retired after 33 years service on 21 December 2007 – somewhat spookily, exactly 365 years after the start of the Siege of Chichester! Mr Blamire noticed part of it sticking out of the ground during the demolition of the old brewery buildings in the mid-1980s. He persuaded the developers to excavate it and put it on a wooden mount outside the entrance to the new offices; where it has stood ever since.

The Armstrong Naval Cannon

At the time several people, perhaps Mr Blamire himself, jumped to the conclusion that it might be a relic of the Civil War.

However, Mr Geoff Smith, an expert on historic cannons from the Ordnance Society, took a long cool look at it in 2014. He has been able to confirm that it is in fact a stock Armstrong Pattern 24-pounder, a British naval gun with a barrel length of 9 feet and a range of 200 yards. The Royal cipher still discernible on it is probably that of George II (1727-1760). He has speculated that it must have lost its way either to or from Portsmouth Dockyard, no doubt falling off its transport into the mire whilst crossing Squittery Bridge. Too heavy to retrieve, it lay abandoned until recent discovery.

There is a final twist. Local historians do speculate that it may well have been discovered earlier than the 1980s, and only survived through the 19th and 20th centuries because some-one thought it would be a great idea to use it as a bollard inside the brewery, as had become the national fashion for the recycling of redundant captured French cannon into road border bollards for our cities, following the victory at Trafalgar in 1805.

It’s a nice idea but no proof can be provided. You will have seen these bollards or their copy everywhere. Usually the cannon were French or later reproductions and the muzzle was stopped with a cannon ball. A trio of fake versions of these kinds bollards can still be seen at the Market Cross on West St. The Westgate cannon however is British, the genuine article and has not been plugged with a cannon ball.